Seán Mac Réamoinn at the Merriman Summer School in 1968. The occasion was the 'turas' - a boat trip to Inis Cealtra on Lough Derg. Photo courtesy of John Horgan (with thanks also to Clare County Library)

At home in Ennis, there is a scrapbook which belonged to Una, my late and much loved aunt. There was a note from her days at UCG, from one Sean MacReamoinn, her fellow-student. "Una, a stor", it read, "is tu a mhairigh mo chiall". If this was even slightly true, Una had much to answer for.

Mac Réamoinn, who died in January 2007, was one of our last links with the postwar generation of radio programme makers. A gifted communicator, he was a passionate man with a consummate sense of the word. He lived his Christianity with urgency and was a memorable colleague, who made an immense contribution to Irish life, culture and broadcasting. It's hard for younger generations to have a sense of the extent to which he shaped the Irish conversation. But he did - liberally, lyrically and wittily. As he himself often said of others, "Ba dhuine uasal é".

There is so much to say about Sean. 'Falstaffian' would only begin to describe him. He was one of my heroes as a teenager, especially for his broadcasts from Rome during Vatican II, which, more crisply than any bishop's pastoral letter, explained the work of the Council to ordinary Catholics. His Catholicism - along with his ecumenism - was deeply felt and I can remember his anguished remonstration on one radio discussion with Joe Foyle, a right-wing Catholic of the day: "Ach cad faoi'n scoilt in eaglais De?" In his day there weren't many like him: he was liberal, Catholic, Irish-speaking, cosmopolitan, and with what Denis Healy calls a sense of 'hinterland'. He was also a socialist - and a passionate member of the then Workers' Union of Ireland (to which radio staff had been recruited by Jim Plunkett). Along with his predecessor as controller, Maurice Gorham, he believed that a true Christian must be a socialist. Indeed I once heard him introduce himself at a public meeting (perhaps it was a Merriman School): "Sean Mac Reamoinn, People of God, Dublin Branch."

At the time, the Irish language was the preserve of some of the most conservative forces in Irish society. Sean - along with people like Liam de Paor and John A Murphy - offered role models for those of us who loved Irish, yet felt ill at ease with the social values that often seemed to come with it. Sean's voice was at once throaty and mellifluous, if that isn't a contradiction, and his command of the spoken word in both Irish and English was a joy. The voice lent itself to caricature: John Keogh's Ray MacSeánmoinn in the satire series Get an Earful of This could be uncannily close to the reality (as indeed was Keogh's 'Sir', Paddy Maguire).

Sean joined Radio Eireann in 1947 from the Department of External Affairs. This was the 'annus mirabilis' (Maurice Gorham's phrase) in which Radio Eireann, then just over twenty years old, acquired a proper staff for the first time (the government of the day had intended to open a short-wave service, a plan which was short-lived, but Radio Eireann got many of the benefits). Sean's generation included Ciaran MacMathuna, Seamus Ennis, Norris Davidson, PP (Paddy) Maguire, Proinsias O'Conluain, men of intelligence and wit, who had a profound sense of the word. Among broadcasters, the only relevant tense is - inevitably - the continuous present, and the contribution of that generation is now fading into history. But it should not be forgotten. Their work was broadcasting's equivalent of Seathrun Ceitinn's Foras Feasa ar Eirinn, or the Down Survey. They created - with great elan -the first sound maps of the Irish cultural landscape.

Then there were the puns. Some of his bon mots can be found on the internet, but the badinage of Madigan's or the Unicorn Minor loses its vividness when reduced to cold text. Two puns I remember which work in print: Sean's sadness at the eclipse of the priest novelist ("We have no Bernanos today"). And there was his complaint to a waiter at breakfast ("This is a very pedestrian croissant"). Not a pun, but I also treasure his fury (voiced to Michael Littleton) at a threatened producers' strike; "I will not tolerate this wild kitten activity." And his riposte to Donal Flanagan in Madigan's who agreed that he would stay on a few more minutes for "a very small Paddy". "Ah well Donal - aren't we all small Paddies in the sight of the Lord." And on his return from Rome to Desmond Williams, who asked him, "How was the Pope, Sean?". "I saw him on Tuesday - and the leg was much better."

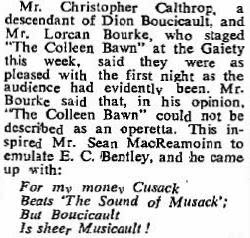

From Seamus Kelly's report of a Dublin Theatre Festival press conference, Irish Times, 10 October 1968.

In the 1950s and 60s he presented a radio series called Around the Town, in its way, a radio equivalent of Terry O'Sullivan's 'Dubliner's Diary' for the Evening Press. The programme was an expression of his personality and instinct for conviviality. More importantly, along with figures such as Padraig O'Raghallaigh and Denis Meehan, he was also one of RTE's 'voices of the great occasion'. In the early 1970s he became the founding head of the radio documentary unit (originally the 'social documentary unit'), which was part of FCA.

Seán had a wonderfully sacramental imagination. He was at the heart of a small Catholic intelligentsia in the Ireland of his time. It included, among others, Louis MacRedmond, John Horgan, Enda MacDonagh and Peter Connolly of Maynooth, the Dominican, Austin Flannery, Kevin O'Kelly, Des Fisher and Garret FitzGerald. That group has, sadly, not had a successor generation (a reproach to Irish Catholicism's inability to move its adherents from a childhood faith to an adult and nuanced version which might endure for a lifetime). He loved the church. He loved the old Irish traditions of faith and he was a passionate advocate of the renewal of the Second Vatican Council. He championed a faith that was at once ancient and modern and raged against the caricature of Irish Catholicism as, essentially, a construct of Italianate devotionalism and Victorian puritanism. "You might as well argue that by combining bad Scotch with Nescafe, you can make an Irish coffee."

.jpg)

Seán had intellect, moral stature and charisma - on the face of it, the perfect leader of the radio service, when Roibeard O'Farachain retired in 1974. One of Sean's talents, and, in a way, his achilles heel, was his spontaneity and gift for improvisation. Wonderful in live broadcasting, of course. And I will never forget the cadences, the poetry and the high dignity of his commentary in Irish on Eamon de Valera's burial in Glasnevin.

But Seán had little taste for organisation and detail; in fact there wasn't an administrative bone in his body. "The only good line is a deadline", he once said, and he wasn't joking. It was his management credo. I remember Michael Littleton's despair when the late-night sponsored programmes were phased out. Despite long warning, Seán could not come to a decision about an alternative. Paddy O'Connor from drama and Micheal O hAodha, the assistant controller (as in Ian Priestly Mitchell's "Our thanks to our producer Mr PJ O'Connor, I'll convey, and to our munificient manager, Mr Micheal O hAodha") tried to cobble together a D Schedule from repeats. With the presses about to roll at the RTE Guide, MacReamoinn summoned up a programme title, Sounds around Eleven , out of midair, and it fell to a furious Michael Littleton along with Kevin Roche quickly to put flesh on the bones (Littleton sensed that what Sean really wanted was "Around the Town" redux).

When Seán had - inevitably - to move on from the controllership, it would be more than a generation before another programme-maker would again run the radio service. But Seán did have his successes. Community radio (his idea) brought RTE into relation with parts of Ireland to which it had not hitherto reached. Corkabout - a Cork area opt-out at midday - was the first local radio service in the country (In 1958, Sean had been the founding head of the Cork studios at Union Quay).

Seán and I worked closely together on the Pope's visit to Ireland, notably on a commemorative LP issued shortly afterwards by RTE. Perhaps just one story from that time. He came back to Donnybrook from John Paul's Mass in the Phoenix Park and asked me puckishly as he settled into a booth in Madigan's "Comrade, why is it that one always feels randy after a great ecclesiastical occasion?"

I lost sight of Seán after I left RTE. He must have found the invention of the mobile phone a liberation, as he was forever on the phone, wherever he was. In Madigan's, he would explode in frustration as the caller in front of him wrestled with Buttons A and B, "If there's anything I can't stand on the telephone, it is a f***ing amateur."

In my BBC years there was one figure who reminded me of Seán. That was Robin Day. Both men had a grand style, rapier like wit, a profound instinct for their respective cultures - and surprisingly similar weaknesses (notably a capacity for self-generated fuss). Neither, I feel, would have found easy acceptance in the world of broadcasting as it eventually became.

Seán Mac Réamoinn at the Merriman Summer School in 1968 (also in shot, Maeve Binchy?). Photo courtesy of John Horgan

Link to Seán Mac Réamoinn obituaries

2 comments:

I last saw Seán at the removal of Fr. Benignus Millet OFM, in Ballybrack. He died soon afterwards.

Great post.

He was also a member of the Welsh Gorsedd of Bards (White order) but not necessarily up to date in his subscription. A mere administrative trivium?

Post a Comment